- Home

- Arturo Islas

Rain God

Rain God Read online

Dedication

For my family – Jovita, Arturo, Mario, and Luis

Epigraph

I come to speak through your dead mouths . . .

Give me silence, water, hope.

Give me struggle, iron, volcanoes.

Fasten your bodies to me like magnets.

Hasten to my veins, to my mouth.

Speak through my words and my blood.

PABLO NERUDA

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Judgment Day

Chile

Compadres and Comadres

Rain Dancer

Ants

The Rain God

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Judgment Day

A photograph of Mama Chona and her grandson Miguel Angel—Miguel Chico or Mickie to his family—hovers above his head on the study wall beside the glass doors that open out into the garden. When Miguel Chico sits at his desk, he glances up at it occasionally without noticing it, looking through it rather than at it. It was taken in the early years of World War II by an old Mexican photographer who wandered up and down the border town’s main street on the American side. No one knows how it found its way back to them, for Miguel Chico’s grandmother never spoke to strangers. She and the child are walking hand in hand. Mama Chona is wearing a black ankle-length dress with a white lace collar and he is in a short-sleeved light-colored summer suit with short pants. In the middle of the street life around them, they are looking straight ahead, intensely preoccupied, almost worried. They seem in a great hurry. Each has a foot off the ground, and Mama Chona’s black hat with the three white daisies, their yellow centers like eyes that always out-stared him, is tilting backward just enough to be noticeable. Because of the look on his face, the child seems as old as the woman. The camera has captured them in flight from this world to the next.

Uncle Felix, Mama Chona’s oldest surviving son, began calling the boy “Mickie” to distinguish him from his father Miguel Grande, a big man whose presence dominated all family gatherings even though he was Mama Chona’s youngest son. Her name was Encarnacion Olmeca de Angel and she instructed everyone in the family to call her “Mama Grande” or “Mama Chona” and never, ever to address her as abuelita, the Spanish equivalent to granny. She was the only grandparent Miguel Chico knew. The others had died many years before he was born on the north side of the river, a second generation American citizen.

Thirty years later and far from the place of his birth, on his own deathbed at the university hospital, Miguel Chico, who had been away from it for twelve years, thought about his family and especially its sinners. Felix, his great-aunt Cuca, his cousin Antony on his mother’s side—all dead. Only his aunt Mema, the pariah of the family after it initially refused to accept her illegitimate son, was still alive. And so was his father, Miguel Grande, whose sins the family chose to ignore because it relied on him during all crises.

Miguel Chico knew that Mama Chona’s family held contradictory feelings toward him. Because he was still not married and seldom visited them in the desert, they suspected that he, too, belonged on the list of sinners. Still, they were proud of his academic achievements. He had been the first in his generation to leave home immediately following high school after being admitted to a private and prestigious university before it was fashionable or expedient to accept students from his background.

Mama Chona did not live to see him receive his doctorate and fulfill her dream that a member of the Angel family become a university professor. On her deathbed, surrounded by her family, she recognized Miguel Chico and said, la familia, in an attempt to bring him back into the fold. Her look and her words gave him that lost, uneasy feeling he had whenever any of his younger cousins asked him why he had not married. Self-consciously, he would say, “Well, I had this operation,” stop there, and let them guess at the rest.

Miguel Chico, after he survived, decided that others believed the thoughts and feelings of the dying to be more melodramatic than they were. In his own case, he had been too drugged to be fully aware of his condition. In the three-month decline before the operation that would save his life, and as he grew thirstier every day, he longed to return to the desert of his childhood, not to the family but to the place. Without knowing it, he had been ill for a very long time. After suffering from a common bladder infection, he was treated with a medication that cured it but aggravated a deadly illness dormant since childhood though surfacing now and again in fits of fatigue and nausea.

“You didn’t tell me you had a history of intestinal problems,” the doctor said, leafing back through his chart.

“You didn’t ask me,” Miguel Chico replied. “And anyway, isn’t it right there on the record?” He had lost ten pounds in two weeks and was beginning to throw up everything he ate.

“Well, I can’t treat you for this now. I’ve cured your urinary infection. You’ll have to go to a specialist at the clinic for the other. And stop taking the medication I prescribed for you.” Later Mickie learned that no one with his history of intestinal illness ought to take the medication the doctor had prescribed. By then, it was too late.

He was allowed only spoonfuls of ice once every two hours and the desert was very much in his mouth, which was already parched by the drugs. Not at the time, but since, he has felt his godmother Nina’s fear of being buried in the desert. Those chips of ice fed to him by his brother Raphael were grains of sand scratching down his throat. In the last weeks before surgery, as he lost control over his body, he floated in a perpetual dusk and, had it happened, would have died without knowing it, or would have thought it was happening to someone else.

There was one moment when he sensed he might not live. As the surgeon and anesthetist lifted him out of the gurney and onto the hard, cold table, each spoke quietly about what they were going to do. Mickie heard their voices, tender and kind, and was impressed by the way they touched him—as if he were a person in pain. He thought in those seconds that if theirs were the last voices he was to hear, that would be fine with him, for he longed to escape from the drugged and disembodied state of twilight in which he had lived for weeks. His uncle Felix had been murdered in such a twilight.

The doctors set him down and uncovered him. He weighed ninety-eight pounds and looked pregnant.

“Your mother is waiting just outside,” said the surgeon’s voice at his right ear.

“I’m going to relax you a little bit so that this tube won’t hurt your nose or throat,” said the anesthetist at his left.

Someone began shaving his abdomen and loins. “God, is he hairy,” said a nurse loudly.

Miguel Chico did not care whether or not he survived the operation they planned for him. When they described it to him and told him he would have to wear a plastic appliance at his side for the rest of his life—a life, they were quick to assure him, which would be perfectly “normal”—they grinned and added, “It’s better than the alternative.”

“How would you know?” he asked. “Let me die.”

Thus, at first he was considered a difficult patient. Later on, the drugs seeped through, drop by drop, and conquered his rebelliousness. When the nurses came in to check on him every twenty minutes and to ask him how he felt, “Just fine,” he would answer, even as he watched himself piss, shit, and throw up blood. Only later, when he survived (“It’s a miracle,” the surgeon told his mother, “his intestine was like tissue paper”), forever a slave to plastic appliances, did he see how carefully he had been schooled by Mama Chona to suffer and, if necessary, to die.

Lying on a gurney in the recovery room, Miguel Chico came to life for the second time. Tubes protruded f

rom every opening of his body except his ears, and before he was able to open his eyes, he heard a woman’s voice calling his name over and over again in the way that made him wince: “Mee-gwell, Mee-gwell, wake up, Mee-gwell.” Another voice from inside his head kept saying, “You cannot escape from your body, you cannot escape from your body.”

He opened his eyes. In the gurney next to his there appeared a fat, strawberry blonde on all fours screaming for something to kill the pain inside her head. “Nurse, give me something for my head!” she yelled without stopping. The nurse, this time a delicate Polynesian dressed in bright green and wearing a mask, glided in and out of his vision.

“Now, now, sweetheart,” she said to the fat woman in a lovely, lilting voice, “you’re going to be all right, and I’ll bring you something in just a minute.” She disappeared with a lithe, dreamy motion.

The fat woman was not appeased and she screamed more loudly than before. He wondered why she was on all fours if she had just come from surgery. Only later did it occur to him that he might have imagined her. At the time, she awakened him to his own pain.

Looking down at himself, he saw that his body was being held together by a network of tubes and syringes. On his left side, by the groin, the head of a safety pin gleamed. He could not move his lips to ask for water, and from neck to crotch his body felt like dry ice, the desert on a cold, clear day after a snowfall. If he had been able to move his arms, he would have pulled out the tubes in his nose and down his throat so that he, too, might shout out his horror and sense of violation. All of his needs were being taken care of by plastic devices and he was nothing but eyes and ears and a constant, vague pain that connected him to his flesh. Without this pain, he would have possessed for the first time in his life that consciousness his grandmother and the Catholic church he had renounced had taught him was the highest form of existence: pure, bodiless intellect. No shit, no piss, no blood—a perfect astronaut.

“I’m an angel,” he said inside his mouth to Mama Chona, already dead and buried. “At last, I am what you taught us to be.”

“Mee-gwell,” sang the nurse, “wake up, Mee-gwell.”

“It’s Miguel,” he wanted to tell her pointedly, angrily, “it’s Miguel,” but he was unable to speak. He was a child again.

* * *

They took him to the cemetery for three years before Miguel Chico understood what it was. At first, he was held closely by his nursemaid Maria or his uncle Felix. Later, he walked alongside his mother and godmother Nina or sometimes, when Miguel Grande was not working, with his father, holding onto their hands or standing behind them as they knelt on the ground before the stones. No grass grew in the poor peoples’ cemetery, and the trees were too far apart to give much shade. The desert wind tofe the leaves from them and Miguel Chico asked if anyone ever watered these trees. His elders laughed and patted him on the head to be still.

Mama Chona never accompanied them to the cemetery. “Campo Santo” she called it, and for a long time Miguel Chico thought it was a place for the saints to go camping. His grandmother taught him and his cousins that they must respect the dead, especially on the Day of the Dead when they wandered about the earth until they were remembered by the living. Telling the family that the dead she cared about were buried too far away for her to visit their graves, Mama Chona shut herself up in her bedroom on the last day of October and the first day of November every year for as long as she lived. Alone, she said in that high-pitched tone of voice she used for all important statements, she would pray for their souls and for herself that she might soon escape from this world of brutes and fools and join them. In that time her favorite word was “brute,” and in conversation, when she forgot the point she wanted to make, she would close her eyes, fold her hands in prayer, and say, “Oh, dear God, I am becoming like the brutes.”

At the cemetery, Miguel Chico encountered no saints but saw only stones set in the sand with names and numbers on them. The grownups told him that people who loved him were there. He knew that many people loved him and that he was related to everyone, living and dead. When his parents Miguel Grande and Juanita were married, his godmother Nina told him, all the people in the Church, but especially her, became his mothers and fathers and would take care of him if his parents died. Miguel Chico did not want them to die if it meant they would become stones in the desert.

They bought flowers that smelled sour like Mama Chona and her sister, his great-aunt Cuca, to put in front of the stones. Sometimes they cried and he did not understand that they wept for the dead in the sand.

“Why are you crying?” he asked.

“Because she was my sister” or “because she was my mother” or “because he was my father,” they answered. He looked at the stones and tried to see these people. He wanted to cry too, but was able to make only funny faces. His heart was not in it. He wanted to ask them what the people looked like but was afraid they would become angry with him. He was five years old.

There were other people walking and standing and kneeling and weeping quietly in front of the stones. Most of them were old like his parents, some of them were as old as Mama Chona, a few were his own age. They bought the yellow and white flowers from a dark, toothless old man who set them out in pails in front of a wagon. Miguel shied away when the ugly little man tried to give him some flowers.

“Take them Mickie,” said his godmother, “the nice man is giving them to you.”

“I don’t want them.” He felt like crying and running away, but his father had told him to be a man and protect his mother from the dead. They did not scare him as much as the flower man did.

A year later, he found out about the dead. His friend Leonardo, who was eight years old and lived in the corner house across the street, tied a belt around his neck. He put one end of the belt on a hook in the back porch, stood on a chair, and knocked it over. Nardo’s sister thought he was playing one of his games on her and walked back into the house.

The next morning Miguel’s mother asked if he wanted to go to the mortuary and see Leonardo. He knew his friend was dead because all the neighborhood was talking about it, about whether or not the boy had done it on purpose. But he did not know what a mortuary was and he wanted to find out.

When they arrived there, Miguel saw that everything was white, black, or brown. The flowers, like the kind they bought from the old man only much bigger and set up in pretty ways, were mostly white. The place was cold and all the people wore dark, heavy clothes. They were saying the rosary in a large room that was like the inside of the church but not so big. It was brightly lit and had no altar, but there were a few statues, which Miguel recognized. A long, shiny metal box stood at the end of the room. It was open, but Miguel was not able to see inside because it was too far away and he was too small to see over people’s heads, even though they were kneeling.

Maria and his mother said that he must be quiet and pray like the others in the room. He became bored and sleepy and felt a great longing to look into the box. After the praying was over, they stood in line and moved slowly toward the box. At last he would be able to see. When the people in front of them got out of the way, he saw himself, his mother, and Maria reflected in the brightly polished metal. They told him it was all right to stand so that his head was level with theirs as they knelt. The three of them looked in.

Leonardo was sleeping, but he was a funny color and he was very still. “Touch him,” his mother said, “it’s all right. Don’t be afraid.” Maria took his hand and guided it to Nardo’s face. It was cold and waxy. Miguel looked at the candles and flowers behind the box as he touched the face. He was not afraid. He felt something but did not know what it was.

“He looks just like he did when he was alive, doesn’t he, Mickie?” his mother said solemnly.

“Yes,” he nodded, but he did not mean it. The feeling was circling around his heart and it had to do with the stillness of the flowers and the color of Nardo’s face.

“Look at him one more time before

we go,” Maria said to him in Spanish. “He’s dead now and you will not see him again until Judgment Day.”

That was very impressive and Miguel Chico looked very hard at his friend and wondered where he was going. As they drove home, he asked what they were going to do with Leonardo.

His mother, surprised, looked at Maria before she answered. “They are going to bury him in the cemetery. He’s dead, Mickie. We’ll visit him on the Day of the Dead. Pobrecito, el inocente,” she said, and Maria repeated the words after her. The feeling was now in his stomach and he felt that he wanted to be sick. He was very quiet.

“Are you sad, Mickie?” his mother asked before saying goodnight to him.

“No.”

“Is anything wrong? Don’t you feel well?” She put her hand on his forehead. Miguelito thought of his hand on Nardo’s face.

“I’m scared,” he said, but that was not what he wanted to say.

“Don’t be afraid of the dead,” his mother said. “They can’t hurt you.”

“I’m not afraid of the dead.” He saw the sand and stones for what they were now.

“What are you afraid of, then?”

The feeling and the words came in a rush like the wind tearing the leaves from the trees. “Of what’s going to happen tomorrow,” he said.

The next day, Miguel Chico watched Maria comb her long beautiful black and white hair in the sun. She had just washed it, and the two of them sat on the backstairs in the early morning light, his head in her lap. Her face was wide, with skin the color and texture of dark parchment, and her eyes, which he could not see because as he looked up her cheekbones were in the way, he knew were small and the color of blond raisins. When he was very young, Maria made him laugh by putting her eyes very close to his face and saying in her uneducated Spanish, “Do you want to eat my raisin eyes?” He pretended to take bites out of her eyelids. She drew back and said, “Now it’s my turn. I like your chocolate eyes. They look very tasty and I’m going to eat them!” She licked the lashes of his deeply set eyes and Miguel Chico screamed with pleasure.

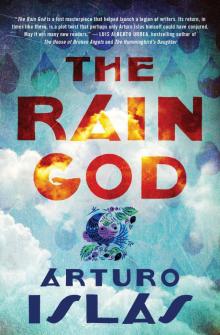

Rain God

Rain God