- Home

- Arturo Islas

Rain God Page 10

Rain God Read online

Page 10

When he realized almost a year later that Lola was not coming back, Miguel went to Los Angeles twice to see her. The first time he told himself that he was leaving Juanita for good, that nothing had changed, that she was still more devoted to others than to him. True, their sex life had improved and she no longer made him feel that he was hurting her all the time, but no experience could be like sleeping with Lola.

Without letting him know, Juanita understood and accepted Miguel’s constant desire for Lola. In her brooding, she decided that even if the experience of a great sexual passion had been denied her, a lasting relationship based on such intense feelings survived only in the movies and bestsellers that she loved. It could not survive daily life. She felt less awed by Lola’s physical power and began, instead, to pity her. She thought Lola was brave to have moved away, yet it pained her that they would never be together again as in the old days.

Miguel’s first trip to Los Angeles, however, shocked her. They had been to a dance sponsored by her club of Mexican women. Miguel referred to them as “the hippos” because they all weighed more than one hundred and sixty-five pounds, but he enjoyed teasing them and trading obscene stories. At the dance he behaved in an unusually courteous manner and even conversed politely with friends and relatives she knew he disliked. They danced every dance together, and she felt pride in demonstrating to them all that she had been able to hold onto her man.

When they got home, they made love. But his silence unnerved her, and while washing herself she listened for signs of discontent. The silence from the bedroom alerted her.

“Anything wrong?” she asked as naturally as she could. He was smoking.

“I’m going to L.A. tomorrow. I have to see her. I’m already packed and I want to get away before six.”

It took her a few minutes to rally.

“But why? Why do you want to bother her now? Leave her alone, Miguel. I thought you were happy again.”

“I have to see her,” he said.

She did not reply. In the morning she prepared breakfast for him, ironed two of his better dress shirts, and, repacking his valise, folded them neatly so that they would not be too wrinkled when he needed them. “It’s almost the holidays,” she said. “Do you have to go now?”

“Yes,” he said.

They were both defeated. After he left, she returned to bed and fought against her bitterness. She, too, had missed Lola terribly and wanted to see her.

Miguel was gone a month, and because of the Christmas festivities and family gatherings it was an especially difficult time for Juanita. She did not know if Miguel would return in time. When she telephoned Miguel Chico to tell him, he said he would not be able to visit after all but encouraged her to spend the holidays in San Francisco. She refused. She lost courage and indulged in fits of weeping and despair.

“I told you,” Nina said two days before Christmas, “your husband is no good.”

“Shut up,” Juanita said sharply. But she was beginning to believe it. She wrote Miguel a letter in care of Lola’s son telling him how disappointed she was in him and that when he returned, as she knew he would, he had better make plans to live elsewhere, because she did not want him in her house. She ended by saying that they ought to think seriously about separating. It was an angry letter and she did not let herself reread it for fear she might repent and not send it.

The day after mailing it, she received a bouquet of flowers from him with a long note saying he now realized that he loved her more than anyone else. Their letters had crossed, and when he returned after the holidays she let him in.

The following autumn, he told her that he was driving to California for the World Series.

“That’s good,” she said, “when are you leaving?”

“Day after tomorrow.”

“I’ll get your things ready.”

Her tone surprised him. No questions, no tears, complete obedience. She knew he would see Lola, but it did not seem to matter to her. She did not even ask when he would be back. He returned five days later, and when he walked into the bedroom she looked up from her book and asked if he had enjoyed himself.

“Sort of.”

“How is she?”

“Okay. She told me to give you her love.”

“That’s nice,” Juanita answered without sarcasm or irony.

He could not bring himself to tell her the truth. Lola had been angry with him for arriving unannounced. They had spent only one evening together, had gone through the motions of lovemaking, and as he left, she had said, “Miguel, call before you come the next time, will you? And give my love to Juanita. Tell her I miss her very much.”

That Christmas, Juanita received a card from Lola.

Dear Juanita!

Thank you for your beautiful card. It touched me deeply, and all I can say is that you are absolutely incredible. I do believe you. I feel the same way about you, and it isn’t because it’s that time of year. I’ve always felt that way. At one time I was very bitter because my name was being smeared all over, but that’s over. Whatever happened, I had coming. Someday, I hope I can get everything off my chest. I know it’s going to hurt, but we’ve all been hurt so much before, maybe it won’t be that bad. I know it’s a hell of a time to tell you this, but I’m feeling brave, so please forgive me. I love you and Miguel very much.

Lola

Juanita showed the card to Miguel Chico, home for the holiday. “What did you say in your note to her?” he asked.

“Oh, I don’t remember. You know, the usual.”

He liked it when she dissembled. It was very uncharacteristic of her and he especially liked that she enjoyed feigning indifference to Lola.

“Mickie,” she said, “please try not to fight with your father this time.”

“You’re starting again, Mother.”

“What?”

“To be a mother. Stop it, I’m too old. I don’t like him and he doesn’t like me.”

“He loves you. He just doesn’t know how to show it very well. But you know he’d do anything for you.”

“Right.”

“He’s been very good to me in these last months.”

“That’s wonderful, Mother. It’s good to know you’re happier now. Remember last Christmas?”

“Don’t remind me. That’s all over and I’m happy now.” She stopped setting the table. “Except.”

“Except what?”

“I wish El Compa were alive and that he and Lola were here with us. Remember those times?”

“Oh, Mother, you are impossible. Didn’t you ever feel like telling her to go to hell?”

“No.”

“You’re too good to be true.”

Juanita laughed. “Tell that to your father.”

Rain Dancer

Felix Angel, Mama Chona’s oldest son, was murdered by an eighteen-year-old soldier from the South on a cold, dry day in February. They were in Felix’s car in a desert canyon on the eastern side of the mountain, and they talked only briefly before the boy kicked him to death. Because of the mountain and the shadows it casts, it was already twilight in the canyon, but on the western side where Felix lived the sun was still setting in those bleak, final moments when he thought of his family and, in particular, of his youngest and favorite son, JoEl.

The border town where Felix spent most of his life is in a valley between two mountain ranges in the middle of the southwestern wastes. A wide river, mostly dry except when thunderstorms create flashfloods, separates it from Mexico. Heavy traffic flows from one side of the river to the other, and from the air, national boundaries and differences are indistinguishable.

Imagining his uncle’s last moments while sitting in his study gazing out at the California dusk settling on the leaves of the birch tree and turning them blue, Miguel Chico felt the sadness of that time of day. There are no sounds in the desert twilight. On very cold or very hot days, the land and its creatures breathe in that dry acid air of the space between day and night and, as the fir

st stars appear, resume their activities in one long exhalation. Felix loved those quiet moments at dusk as much as the smell of the desert just before and after a thunderstorm when the sky, charged with lightning, became fresh with the fragrance of the mesquite, greasewood, and vitex trees. He had never been able to describe the smell until one day JoEl, not yet five years old, had said, “They’re coming. I smell them.”

“Who? What are you talking about?”

“The angels.”

“You mean the family?” Felix asked.

“No. The ones in the sky.”

From then on, JoEl could tell them when it was going to rain.

When Felix was a child he would run outside and dance when the storm clouds passed over, while his brothers and sisters hid under the bed. Neither Mama Chona, nor later his own family, could stop him.

“You’ll be struck by lightning,” they said.

“Good. I’ll die dancing.”

Felix and the young soldier had met in a bar around the corner from the courthouse. The bar serves minors and caters to servicemen and has enough of an ambiguous reputation to be considered an interesting or suspicious place by the townspeople on the “American” side of the river. Usually, afraid to be seen in such places, the citizens north of the river went to the dives and nightclubs across the border in search of release or fantasy and returned to their homes refreshed, respectability intact, like small-town tourists a little hung over after a week in New York or San Francisco.

But Mama Chona’s son Felix was not a respectable man. Constantly on the lookout for the shy and fair god who would land safely on the shore at last, Felix searched for his youth in obscure places on both sides of the river. He went to the servicemen’s bar regularly after work at the factory. On payday he treated everyone to a round of drinks, talked and laughed in jolly ways, and offered young soldiers a ride to the base across town, especially when he paid visits to his mother’s sister, Tia Cuca, out in the desert.

Felix had been irritable that day because of his argument with JoEl at the breakfast table. Ordinarily he approached his work and even the difficult disputes between laborers and bosses with a casual good humor his comrades at the plant appreciated. He had been a graveyard shift laborer when his daughters, Yerma and Magdalena, were very young, but after Roberto and JoEl were born he was promoted to regular shift foreman. In the last five years he had been put in charge of hiring cheap Mexican workers. He had accepted the promotion on the condition that these men immediately be considered candidates for American citizenship and had been surprised when the bosses agreed. After thirty-five years, he was content with his work at the factory.

The Mexicans he hired reminded Felix of himself at that age, men willing to work for any wage as long as it fed their families while strange officials supervised the preparation of their papers. As middleman between them and the promises of North America, he knew he was in the loathsome position of being what the Mexicans called a coyote; for that reason he worked hard to gain their affection.

A person of simple and generous attachments, Felix loved these men, especially when they were physically strong and naive. Even after losing most of his own hair and the muscles he had developed during his early years on the job, he had not lost his admiration for masculine beauty. As he grew older that admiration, instead of diminishing as he had expected, had become an obsession for which he sought remedy in simple and careless ways.

Before they were permitted to become full-time employees, the men were required to have physical examinations. These examinations, Felix told them, were absolutely necessary and, if done by him, were free of charge. He scheduled appointments for them at his sister Mema’s place across the river. The physical consisted of tests for hernias and prostate trouble and did not go beyond that unless the young worker, awareness glinting at him with his trousers down, expressed an interest in more. The opportunists figured that additional examinations might be to their advantage, though Felix did not take such allowances into account later. In those brief morning and afternoon encounters, gazing upon such beauty with the wonder and terror of a bride, his only desire was to touch it and hold it in his hands tenderly. The offended, who left hurriedly, were careful to disguise their disgust and anger for fear of losing their jobs. He could not find words to assure them. In most cases, however, the men submitted to Felix’s expert and surprisingly gentle touch, thanked him, and left without seeing the awe and tension in his face. It did not occur to them that another man might take pleasure in touching them so intimately.

Later, after the men were secure in their work, the more aware among them joked about the examinaciones and winked at each other when Felix passed by on his way in and out of the office. None but the most insecure harbored ill will toward him, because his kindness, of which they took advantage on days when they were inexcusably late or absent, was known to all. A few, feigning abdominal pains, returned for more medical care and found themselves turned away. Most forgot the experience, occasionally referred to him behind his back but affectionately as Jefe Joto, and were grateful for the extra money he gave them for the sick child at home.

On the day of his morning argument with JoEl, Felix had not responded to any of his men in the usual friendly manner. In an attempt to tease him out of his mood, one of them talked loudly about the phases of the moon. Felix stared at the man.

“Hey, Jefe, it was only a joke.” The young Mexican pronounced the English “j” like a “y” and Felix said to him angrily, “Hey, pendejo, why don’t you stop being a stupid wetback and learn English?” Then, murmuring an apology, he walked toward the man as if to embrace him, gave him a strange look, and walked away.

Any disagreement with JoEl caused Felix to be irritated with everyone, even his wife Angie toward whom he felt the kind of tenderness one has for a creature one loves and injures accidentally. He was unbearably ashamed of his remarks to the young laborer. Alone in his office at the noon hour, eating the burritos Angie had prepared for him, he choked on his shame.

The beer at the bar was good enough to restore his spirits and it began to give him the calm he needed to mull over his quarrel with JoEl. Felix loved young people and did not understand why his son did not see that. Now that JoEl was fourteen and more rebellious than ever, their arguments became nightmares during which Felix said words he did not mean. JoEl replied in curt, distant phrases that cut him off and caused anger to rise from his belly into his throat with a vehemence that caught him off guard. Their arguments never directly confronted the deeper antagonism that had begun to grow between them. Sometimes, even without speaking to each other, the tension was so palpable that one of them was forced to leave the room.

“But I want to go on that trip,” JoEl had said harshly.

“I don’t have the money to give you for it,” Felix answered in the same tone.

“You have the money for beer and for Lena whenever she wants it.”

“Your sister is older than you and needs it for important things, not for football trips with gringos.” Felix liked gringos and football. Why had he said that?

“Oh, yeah,” JoEl replied, “important things, huh? Like a phony pearl necklace for her date with that pachuco she’s been seeing.”

“He’s not a pachuco. He plays in the band she sings with, and it’s important for her to look nice. She’s got talent.”

“She’s got talent, all right.” JoEl’s face had been ugly when he repeated the word.

—My beautiful son, don’t look like that. It will wrinkle your face like a prune and your eyes will harden and break my heart.

Felix saw JoEl’s eyes floating in the warm darkness of the bar. He would borrow money from his younger brother Miguel Grande, who would lend it without any questions or conditions. Felix felt the cold air of the desert winter as someone came into the bar, but the glare from the light outside blinded him so that he saw only the silhouette of a young man in uniform cross the threshold. JoEl’s eyes disappeared into the far corner of t

he room.

* * *

Felix and his first son Roberto did not quarrel. Berto, who was Angie’s favorite, was happy and easygoing—not a thinker like JoEl—and they all enjoyed his company. He helped his father fix the car whenever anything went wrong with it and would talk to him quietly about his problems with girls. He was dark-skinned like his mother, very “Indian,” polite and shy. Felix returned his love in a steady, uncomplicated way. Only JoEl, antagonism causing his cinnamon eyes to seem darker, persistently disagreed with Felix about almost everything.

“You are just like your father,” Angie told him. “Stubborn and too proud for your own good.” She spoke English with a heavy Mexican accent and used it only when she wanted to make “important” statements, not realizing that her accent created the opposite effect. After his first year in school JoEl learned to be ashamed of the way his mother abused the language. The others, including Felix, loved to tease and imitate her. Their English was perfect and Spanish surfaced only when they addressed their older relatives or when they were with their Mexican school friends at social events.

“Come on, Mother, say it again,” Magdalena pleaded.

“No seas malcriada” Angie said and waved her hand close to Lena’s cheek.

“No, Ma, not in Spanish. Say it in English.” Lena and her summer boyfriend were on the front porch, seated side by side hardly touching, swinging slowly back and forth. Every night at exactly nine-thirty, Angie went to the screen door behind them and said, “Magdah-leen, kahm een.” Lena shrieked with delight; the sad boyfriend smiled apprehensively.

“Oh, Mamá, just a few more minutes.” She said “mamá” in the Spanish way.

“No, señorita. Joo mas kahm een rye now.” More howls, as the boy said an embarrassed good night and slipped from the swing and the porch into the dark. Lena barely noticed. She was too taken up by her mother, whom she adored.

Of his two girls, Lena was more like his wife, small and dark, with eyes like JoEl’s. From his room in the back on those hot desert nights, Felix loved hearing the women talk and laugh after the boyfriends left, and he followed them in his reveries before sleep as they walked arm in arm from the living room to the kitchen spraying mosquitoes and turning off lights.

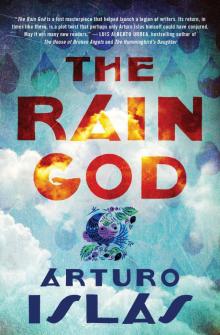

Rain God

Rain God