- Home

- Arturo Islas

Rain God Page 6

Rain God Read online

Page 6

Miguel Chico sat next to him without feeling restless or uncomfortable, joined in their fun without hesitation, and took sides against Miguel Grande. Juanita liked to see her son laugh. He was becoming much too serious at the university and she did not know what to do about it. The long estrangement between him and his father, for which she felt partially responsible, continued to disturb her. She watched El Compa embrace her son every time he and Lola won a hand. When he was especially elated, he kissed Miguel Chico with great affection, telling him how proud they were of his accomplishments in that big deal college so far away. Juanita noticed that Miguel Chico allowed El Compa to express his feelings without embarrassment, and this pleased her.

“Come on, fairy, let’s go home,” Lola said to El Compa. His expansive spirit was known and accepted by all with pleasure, but Lola enjoyed teasing him about his affection for other men. As they left, Lola embraced Juanita and Miguel Grande. She kissed Miguel Chico on the mouth. It annoyed him when she forced her tongue between his teeth.

Lola’s and El Compa’s three years together ended when El Compa died of a heart attack trying to keep the desert out of her kitchen. After the funeral, Juanita went into her own kitchen, opened the cabinets, and threw out all of her old dishes. She replaced them with the elegant white china she had purchased for herself as an anniversary gift. “What am I waiting for?” she said to Miguel Grande. “Life is too short. Why am I saving the luxuries for later? It is later.”

Miguel Grande did not hear her. He walked past her to the bedroom, El Compa’s badge in his pocket. He tried to take a nap but failed because he could not get Lola out of his mind.

It began at the rosary for El Compa when he saw her in a black dress that showed off her figure. Her eyes were shining without tears. “The black widow,” he thought to himself and grinned. Lola caught his eye in that moment, then turned in the direction of the casket. Miguel’s stomach began gnawing on his heart.

Lola hated death and everything connected with it. Her instinct was to let the dead die. She was sorry and saddened because El Compa was a good man and had not enjoyed his success long enough, but her passion for him had been realized and spent. Mourning him would not equal the time of hurt she had spent waiting for him to love her. They had had three good years. She was sorry for herself that they had ended so abruptly.

Lola could not bear the weeping women around her. Why should she pay homage to the dead? Even Juanita’s blubbering made her impatient. El Compa would be laughing at them all with her now, only in a more kindly way, for he was always nicer than she. She resented the role she must play in this room full of prayers for the made-up thing lying in a quilted box. It was too ridiculous. Frank Jr., standing on the other side of the casket with the men, stared accusingly at her. Lola felt nothing toward him and looked at Miguel Grande instead. His slight grin made her want to burst out laughing and she turned quickly toward the casket.

I don’t like you this way, Compa. I don’t like you this way at all. Who are all these women in black? They hardly ever speak to me. I’ve never been respectable enough for them. There’s your mother and your old mother-in-law with her. They never liked me. I hate their black veils and their dark brown stockings and their age. The hypocrites make me sick. They loved you until you married me, then they weren’t so loving. Hard bitches, I don’t believe a single tear. And what does that priest care about you? You were nothing to him and he was nothing to you. What is all this droning about? For what? There’s that big joto Felix. At least the fairy doesn’t care what all these people think about him. You liked him too, my Compa, but why is he moving his mouth like an idiot? And that little prig Miguel, what’s he doing here? At least he’s not praying. His father’s after me already, but I wouldn’t mind teaching the kid a few things. It might take that sour look off his face. I want to get out of here, Compa. I’m suffocating. All these words over and over are suffocating me. If I grab Juanita’s arm real hard, she’ll stop crying and pay attention to me.

“What do you want? What’s the matter?” Juanita did not like the expression on Lola’s face. She was afraid her friend was going to scream.

“Nothing.”

After the rosary, Lola, the two Miguels, and Juanita waited for everyone else to leave. Juanita held her breath as El Compa’s mother and Mrs. Cruz, Sara’s mother, walked toward Lola to express their grief. They were escorted by Frank Jr. The last time they had talked, El Compa’s mother had told Juanita that she would never again speak to “that woman.” Juanita knew it was futile to attempt to make peace between them; Lola’s pride would not permit it. The old woman, white haired, slim, and elegant, approached them slowly. Sara’s mother, on Frank Jr.’s arm, was a few steps behind her. The two women had just finished paying their last respects in front of the casket, and Juanita had watched Mrs. Glass touch her son’s face. Juanita was not afraid of Mrs. Cruz, but she gave plenty of room to the woman who had buried two husbands and now her only son. Mrs. Glass’s eyes, like her voice, were dry.

“Juanita, how are you?” She spoke in Spanish. “And you, Miguel and Miguelito? How happy I am to see you always, whatever the circumstances. Come and visit me at home next week, will you? I want to talk to you.” Juanita mumbled inaudible replies and very carefully directed her toward Lola, who was standing by the door of the mortuary. Mrs. Glass walked in a measured and solemn way, staring hard at Lola, as she passed her by without a word. Sara’s mother nodded shyly at her and said very softly in Spanish, “I’m so sorry.”

Lola held her back. “I am too, Señora Cruz.” Juanita hoped Lola would stop there. “But I am happy to know that today El Compa is with Sara.” Mrs. Cruz embraced Lola without looking to Mrs. Glass for permission, and they walked out of the mortuary together. Frank Jr. and Mrs. Glass were waiting for them at the bottom of the stairs. Refusing to respond to the sound of his mother’s name on Lola’s lips, Frank Jr. noticed how well made-up she was and, to make sure she had no chance to kiss him, quickly took his grandmother’s hand and helped her into the car. Lola ignored Mrs. Glass completely.

She knew the effect her words would have on Sara’s mother and was pleased to have gotten even with Mrs. Glass for snubbing her. In fact, Lola was not glad that her man was out in the pure serene with his first wife. If they were floating around somewhere, disembodied spirits, she was jealous. Only the thought that they couldn’t have sex consoled her.

“What a beautiful thing you said to Mrs. Cruz, Lola. I thought you were going to put your foot in it,” Juanita told her as Miguel drove them back to El Compa’s house.

“That old fool. What do I care about her? She thinks that one hug can make up for all the insults they’ve made behind my back all these years.”

“She’s never said anything about you. You’re being unfair.”

“Well, it’s the same thing. She never came to see me or invited me to her house. Every time I invited her, she refused. Anyway, who cares about those old ladies? They loved taking all that crap from their men so that they could act like martyrs after the men died. I don’t like old bags who wear black all the time. El Compa’s death is going to give them another excuse to suffer for a plaster god who doesn’t give a damn about them or their moaning. Why aren’t they dead? My Compa is gone. He was young. What are they doing still alive?”

“They ask themselves the same thing, Lola.” Juanita replied quietly, suppressing her opposition even though she did not like Lola’s tone or her lack of respect for religion and old people. “Why don’t you cry?” she asked before she could stop herself.

“Because I’m not mad enough,” Lola answered in a hard tone.

Miguel Chico was shocked. Miguel Grande smiled to himself as he saw them reflected in the rearview mirror. He asked himself how he could live without them. Together, they made him happy and filled his life.

His passion for Lola began in that way. The look they had exchanged during the rosary planted the seed of longing for her in that place near his groin and heart where he

was most vulnerable. He already knew how she made love. Years before he had taken her to bed and had recognized her as an equal there. Once that was settled, he had been content to let it rest, especially after she and Juanita became so close. But now with El Compa gone, something had changed. There was a shift he neither understood nor knew enough to fear, in a direction toward which a soft wind was blowing, scented with her perfume. Years of indulgence in the flesh of beautiful women, like all those years of smoking, did not help him turn away from Lola and her scent. Instead, they helped him sniff her out, discover her most vulnerable place, and show it to her. The revelation ruined the three of them for a time.

Miguel Chico, riding in the front seat with his father, began to feel sick to his stomach. He hated the smell of cigarette smoke, and the summer night made it hang heavy in the car even with the windows open. Lola and his father smoked all the way to her house. The tools El Compa had used still remained on the roof because Lola refused to let anyone touch them. As they walked to the door, Miguel Chico fought his nausea. Finally, he went to the toilet and vomited. Juanita, accustomed to his weak stomach from birth, was not troubled. Lola knocked on the door and offered him a glass of water.

“No, thank you,” he said as impersonally as possible. He feared her power and could not stand her touch.

“All right, baby, I’ll leave it right here on the table by the door. It’s got ice in it, and it’ll help to settle your stomach.” He waited until he heard her walk away before he opened the door and drank the water in gulps. It gave him cramps and he sat down on the toilet waiting for them to pass.

“Mickie, let’s go,” his father shouted from the living room. He was never sick and he ignored the illnesses of others.

“I’ll be right there,” he answered. There was blood in his stool.

“Are you sure you want to stay alone tonight?” Juanita asked Lola as they were leaving. “You know you can come over to our house.”

“I’ll be all right. I need to be by myself after today,” she said. Miguel Chico watched as his parents, first his mother, then his father, hugged her.

After El Compa’s death, Lola regularly began calling Miguel Grande to her house across town to help her with mechanical chores. He stopped up the cracks in the roof and the desert shifted from the kitchen into her heart. She was always thirsty. Her friendship with Juanita did not seem strong enough to withstand her greater need for the love of a man, and her conscience, long since discarded, seemed lost forever.

“Listen, comadre, is Miguel there?”

“Yes, comadre, what do you need?”

“You know, there’s always something wrong with something. This time it’s the garden hose. Can you ask him to come over and fix it?”

“Sure. I’ll send him right over.”

As she hung up the phone, Lola asked herself what she thought she was doing, but not in any serious way. Not until she had fallen in love with him did she feel afraid of what might happen to all of them.

In the meantime, she enjoyed her moments with him. Their lovemaking, which they arranged easily, left them exhausted but never satiated. On weekends they all spent time together, and Lola often slept in Mickie’s room when he was away at school. Juanita’s other friends began to warn her, but she remained loyal to Lola.

“Look, comadre, your little friend has no shame. You’d better keep an eye on her. She’s after your husband.”

“I don’t believe it and you’d better stop telling me such things or we won’t be friends any more. She’s my friend and I trust her.” In Juanita’s mind, El Compa was still alive and keeping Lola company. To think that her best friend would betray his memory with her husband was beyond the possible to her.

So Lola, Miguel Grande, and Juanita went to parties, movies, and dances together. Miguel began guarding Lola closely when she danced with other men, and after such occasions they fought vehemently.

“I saw the way you were dancing with that queer Pepe.”

“Oh? He’s a very good dancer. And he’s no queer.”

“How would you know? All good dancers are queer and you know it.” Miguel shared the macho’s distrust of any man who was too handsome or danced too well. “Did he spend the night here?”

“Hey, Miguel, that’s none of your business.” Lola tried to speak in a matter-of-fact tone, but she was getting more and more angry with him and she knew she was lost if she showed her anger.

“Well, you didn’t have to kiss his ass all night.”

“I don’t kiss anybody’s ass, Miguel. And I can do anything I want to. We’re not married, remember?”

He stared at her with rage. He could not understand how she could speak to him like that. He wanted to kill her and felt she should be begging him for mercy after all he had given up for her. He did not know why he couldn’t bring himself to tell her that the things she did hurt him deeply.

When he forced her to the couch she knew she had won. Men were easy to deal with sexually. Without a word and very quickly she took off her clothes, and he was at her. Her knowledge of these mysteries helped her say several times without meaning it, “Hurt me, Miguel, hurt me.” She moaned as if indeed he were and, in that way, gave him the illusion that he was in control once again.

Nina was aware of their games after she saw them dance at the twenty-fifth wedding anniversary party. At the weekly poker games, she observed carefully the ways in which Miguel Grande was attentive to Lola. At first she attributed it to his concern for her well-being after El Compa’s passing. After the anniversary celebration, she knew better.

It was the way Miguel lit Lola’s cigarette that confirmed Nina’s suspicions. He made a point of the gesture, causing an infinitesimal lull in the game as he stopped to attend to Lola’s needs. And he did it with a grace Nina had never noticed in him, certainly a grace he did not extend to her sister whose wants he saw to with care, but casually or with constant complaining. The motion of his arm, lighter in hand, and the way Lola drew the flame toward her face, her own fingers resting in a silky way on his, the instantaneous meeting of their eyes and the just-as-instantaneous return to the cards as Miguel clicked the flame out without blowing on it as he usually did. The entire ritual fascinated and disgusted Nina.

How dumb do they think I am, she asked herself, and tested her observations by asking her brother-in-law to light her own cigarette. He did so without ceremony and as always. Nina stopped looking at her cards in order to set firmly in her mind the full implications of his gesture. Such evidence would come in handy when Juanita discovered for herself what was going on. From experience, Nina knew it would take her unworldly sister a long, long time, for she trusted everyone and everything.

“What are you doing with those cards, stupid?” Lola asked Miguel, and everyone at the table laughed. She alone got away with belittling him in front of others without having him retreat into hurt masculine pride. “Deal and get it over with.” Nina noted the honey in her voice.

As he dealt, Miguel commented on every card, a habit of his that drove Nina to distraction. “A trey, a deuce, a queena, a joto, a five-a, an eighter from Decatur, and an ace for me.” Only it wasn’t, it was just a four. Nina was glad. The queen was hers and she bet three cents on it knowing that Miguel would raise it to a nickel. “Un neekle,” he said, too impatient to wait for the others to throw their money into the pot.

“All right, the boat’s loaded. Pair of treys for Juanita.”

“Ay, how good,” Juanita said. She was sitting on his left and Lola was on the other side of him.

“A ten for sourpuss.” Nina’s husband, out a dime, picked up his cards and slammed them down in real disgust, wondering out loud why he had such terrible luck and vowing to quit playing poker altogether.

“Oh, Ernesto, don’t be such a spoilsport,” Lola said, but she failed to seduce him back into the game. Nina watched her carefully from across the table.

“Pair of queenas for the Nina.”

“Tenk joo berry mahch,�

� she said in a hammed up Mexican accent.

“There’s a six for your joto, Memo.”

“Thanks,” the lifelong poker friend answered, “let’s see if they can make it together.”

His wife Carla snickered. She drank too much and took a long time figuring out what cards she held. She won often.

“Possible straight,” Miguel said to her.

“And a king for the widow.” Lola glared at him warmly and then looked around him at Juanita to make sure they both disapproved of his lack of respect for the dead. She was protecting herself nicely, Nina saw.

“And an ace!” This time it was. “And I bet another nickel.”

“I’ll bet three cents.”

“To a nickel,” he said immediately.

“Of course, I knew you’d do that,” Nina replied.

“Why don’t you raise me? You’ve got a pair of queens.”

“Because you’ll raise me after.”

“No, I won’t.”

“Yes, you will.”

“No, Ninita, I promise. Trust me,” he said in his most charming voice.

“Okay. Three more cents.”

“To a nickel!” he upped the bet quickly.

“I knew it, you big liar.”

Nina loved these games. Cards excited her, and winning at poker or blackjack was one of her great pleasures. Her thrill came in watching Fortune at work in such tangible ways, and her pulse quickened at the turn of each card as they drew closer to the end of the deal. Her queens held steady; she knew she had some chance in seven card stud, nothing wild. Juanita was still in the game with two threes showing. Lola had a possible high straight. Memo and Carla were out and Miguel just had that one fat ace showing and not much else. He was such a bluffer, she knew he had nothing underneath to back it up.

“Your bet, sweetie-pie,” he said to her.

“Wait a minute. I’m thinking.”

“You’re not here to think. You’re here to play poker.”

“Oh, leave her alone,” Lola and Juanita said at the same time. Nina was unable to concentrate on the cards because she was overwhelmed by the spectacle across the table from her. For the first time, she wanted to break her resolve and warn her sister.

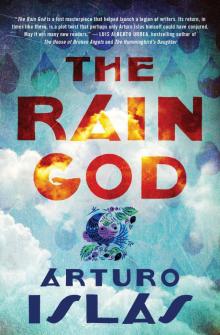

Rain God

Rain God